Substack Essay Series #1: The Strange Story of Me, Shia LaBeouf, and the War Between Old Media and New Media (Part I)

For reasons I still don't understand, Columbia Journalism Review recently published a passel of lies about me and LaBeouf. In this personal essay, I set the record straight.

{Note: This is Part I of a multi-part essay on the ongoing debate between major media and independent journalists working on Substack about whether the former is confirmably more reliable. Part II of this essay is here; Part III is here; Part IV is here; and a coda is here.}

Introduction

Of late, there’s been a public debate, initiated by UCLA professor Sarah Roberts, over the accuracy of independent journalists writing on Substack versus the accuracy of institutionalized major media. As every working journalist has their own method of responding to what they perceive as a smear, the past few weeks have seen different sorts of responses to Roberts’ rant against Substack, from an angry response by Matt Taibbi to an even-handed essay by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), from podcast comments by Katie Halper (reported on by Rolling Stone) to my own failed attempts to get Roberts to respond coherently to critiques of her claims. After Roberts falsely claimed she didn’t follow me on Twitter, I provided proof that she did, and after she falsely accused me of “engag[ing] in a contract [with Substack] simply to be present on the platform”—I’ve never communicated with anyone at Substack—Roberts, who to that point was responding to me regularly, disappeared from sight.

It would be easy enough to settle for just this one amusing public irony—a smug, self-appointed defender of fact-checking and major media getting fact-checked in real time by a journalist she has criticized, and immediately running away when it is revealed that she has both lied and made a serious allegation with no proof whatsoever—but my way of responding to dishonest cranks like Roberts is based on my own poetics, which means that I’m going to (a) tell a story in response, and (b) bring receipts in doing so. It’s what I’ve done for all of my 27 years in journalism, ever since I became a reporter for the nation’s oldest college newspaper, The Daily Dartmouth, at seventeen.

“Poetics,” which Columbia Journalism Review reports is a term of my own derivation, is, as CJR was told repeatedly prior to publishing a recent article on me, nothing of the sort. CJR’s fact-checker, who asked me about this subject before my corrections were overruled by CJR, was told by me that the term has been prevalent in academia for decades; that multiple universities, including University at Buffalo and University of Notre Dame, even offer graduate degrees in the subject; but institutionalized major media today is so certain it will be trusted based on its brand rather than its content that CJR went ahead anyway and attributed to me a term Aristotle wrote a book on 2,351 years ago, in approximately 330 BC.

The most regrettable part of this is that I told the CJR fact-checker, Andrea Cruzado, that it would be professionally embarrassing to me as a professor who teaches (among other subjects) rhetoric and composition if CJR contributor Lyz Lenz, due to her own obliviousness to the term—she asked me to define it when I last spoke to her, in 2020—pretended that I had coined it. Nothing in this plea kept CJR from doing what it planned to do all along:

In the courses I teach on poetics at University of New Hampshire, a flagship public university with an R1 designation for “very high research activity,” poetics is defined as “the idiosyncratic relationship a written or oral communicator develops with language, culture, genre, and self-identity, as inductively produced over one’s lifetime by dozens of discrete factors, including one’s knowledge bases, skill-sets, hobbies, passions, obsessions, preoccupations, experiences, relationships, triumphs, traumas, temperament, genetics, language acquisitions, and more.” I told Cruzado that under no circumstances whatsoever could it be equated to mere “personality.” In the end, however, Lenz—who had never heard the word “poetics” before—substituted her own feelings for the expert opinion of a professor who teaches classes on poetics at an R1 university. This is roughly the state of institutionalized major media in 2021.

But let’s get to the meat of the story.

Shia LaBeouf

In 2013, actor Shia LaBeouf was embroiled in a plagiarism scandal that threatened to derail his career. The scandal only deepened when it was revealed, in December 2013, that LaBeouf had plagiarized his apologies for plagiarizing. I was fascinated by this latter maneuver—I’d never seen anything like it before—so in the first week of January 2014, I sent a draft of an essay about LaBeouf to my Indiewire editor, Max Winter. At the time, I was a paid columnist for the popular and well-respected culture website, where I ran a regular column on metamodernism—the first such column in the United States.

Here’s the email my editor Max Winter sent me back on January 9, 2014:

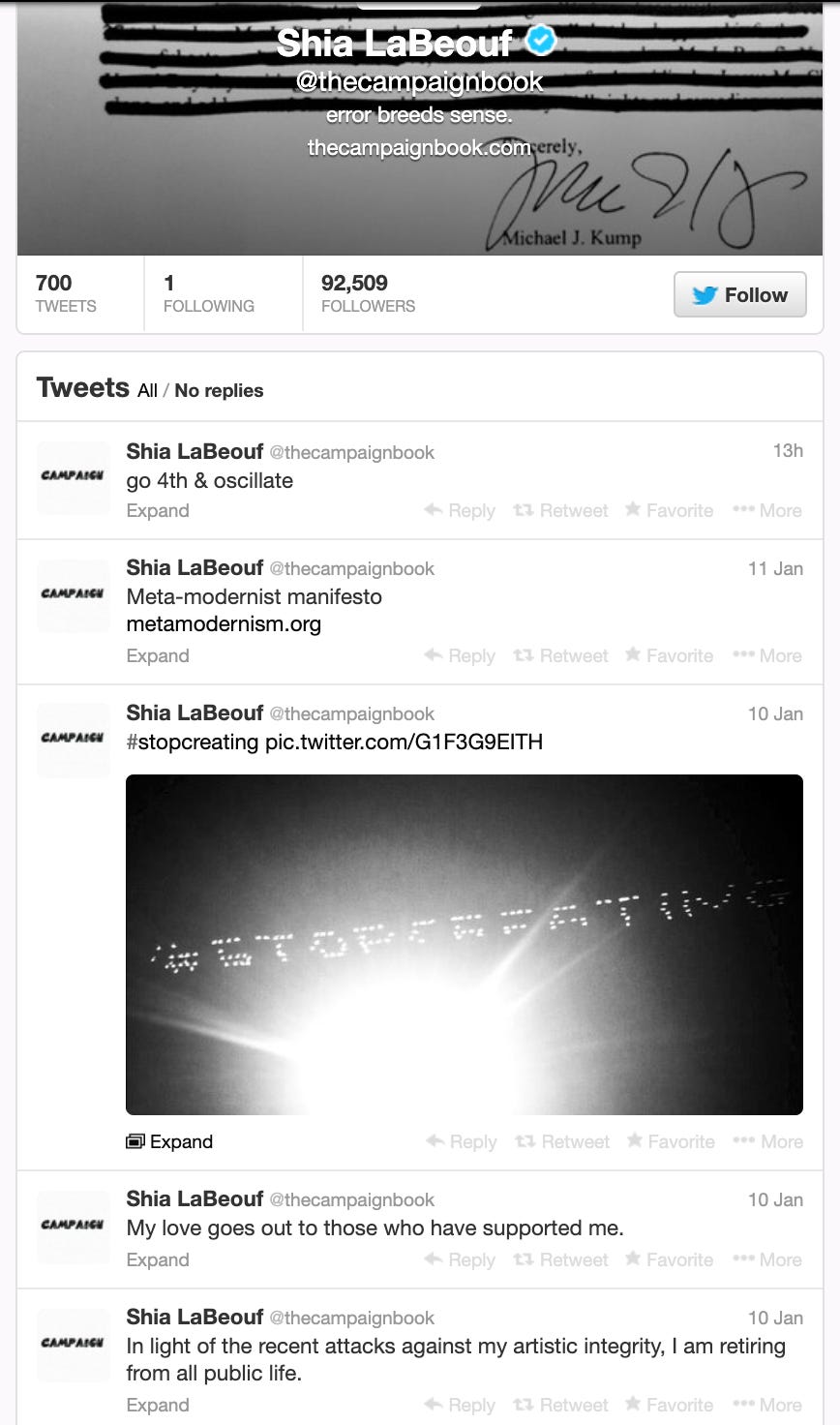

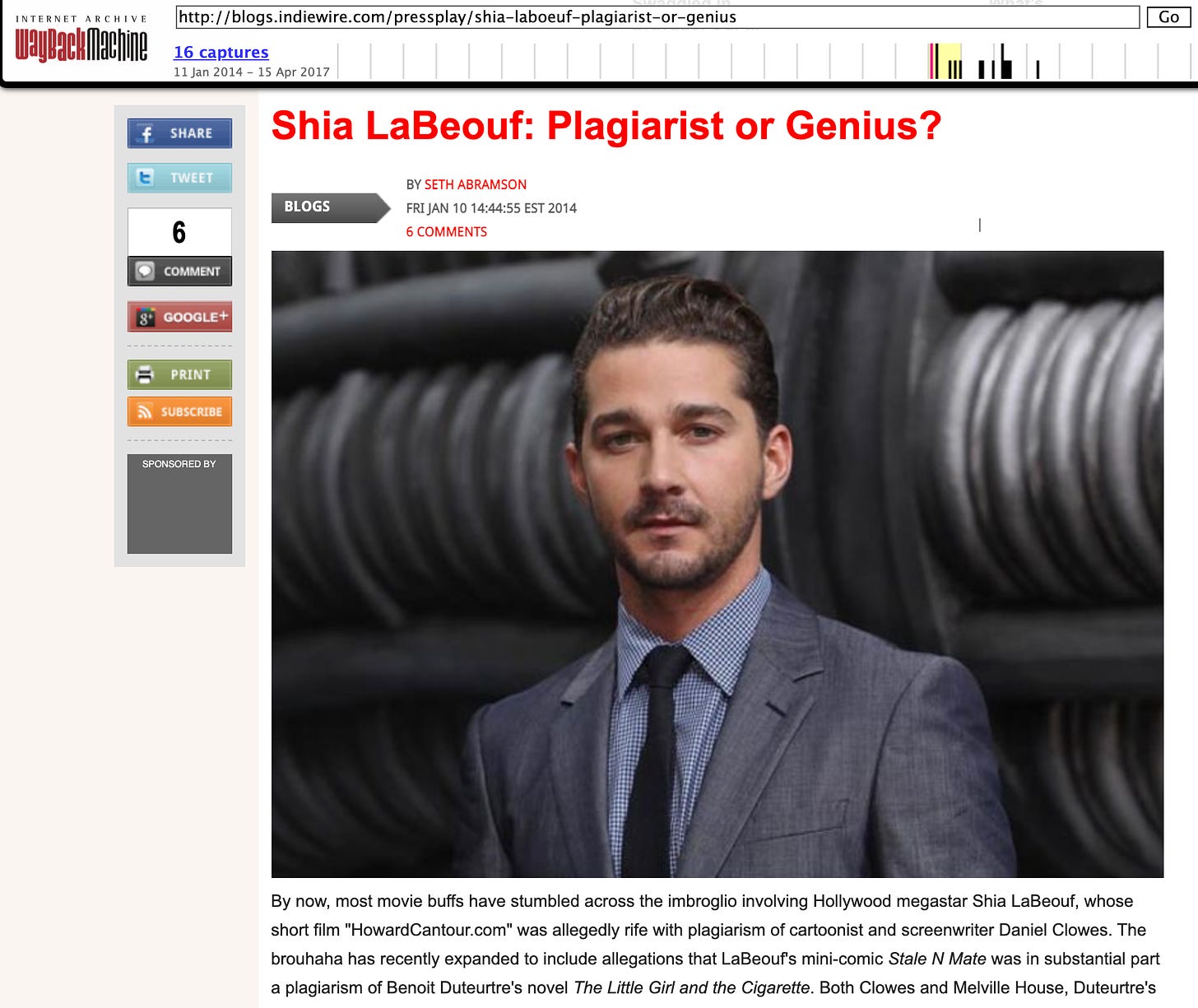

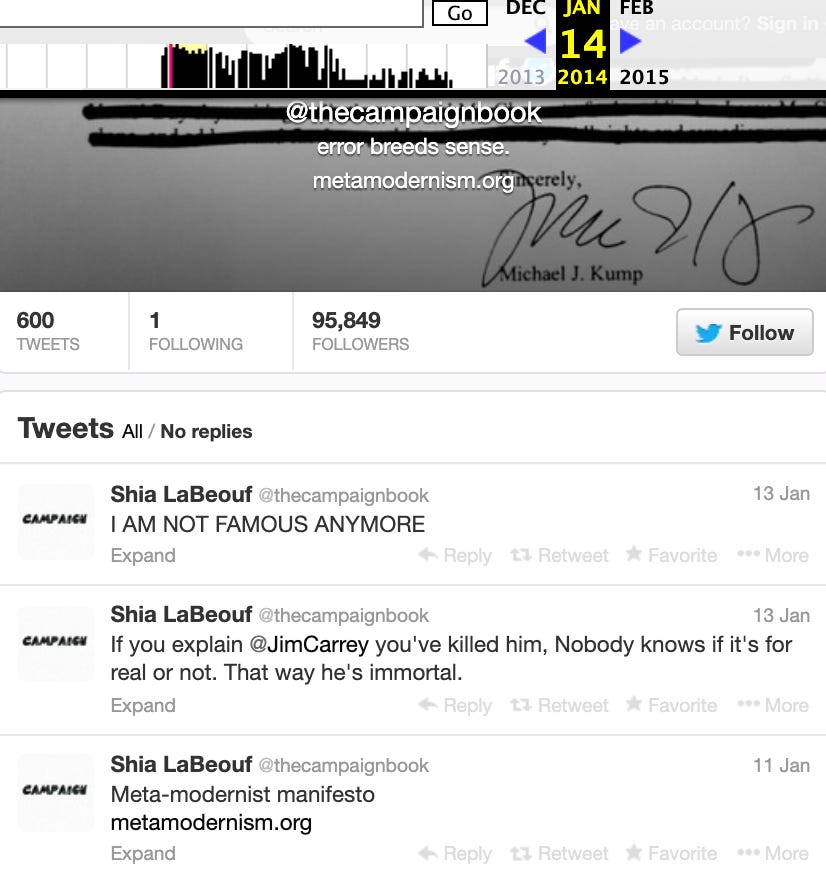

Little did I know when I wrote the essay, titled “Shia LaBeouf: Plagiarist or Genius?”, that LaBeouf would announce on Twitter the following day—January 10, 2014—that he was “retiring from all public life” because of attacks on his “artistic integrity” (see screenshot below). It became clear in that moment that LaBeouf was at one of the lowest moments of his life, ready to throw away his career because his attempt to “#stopcreating”—a hashtag he unsuccessfully tried to get trending on January 10 as a means of justifying not creating original work but using the work of others (see below)—had been rejected by media and fellow artists alike. Even a photograph of LaBeouf’s hashtag being pulled behind a plane that LaBeouf had paid for (see below) failed to get him out of the hole he found himself in.

My article for Indiewire ran on January 10, the very day LaBeouf “retired” (so he said) from public life. Here’s a screenshot, for those who don’t want to click the link above:

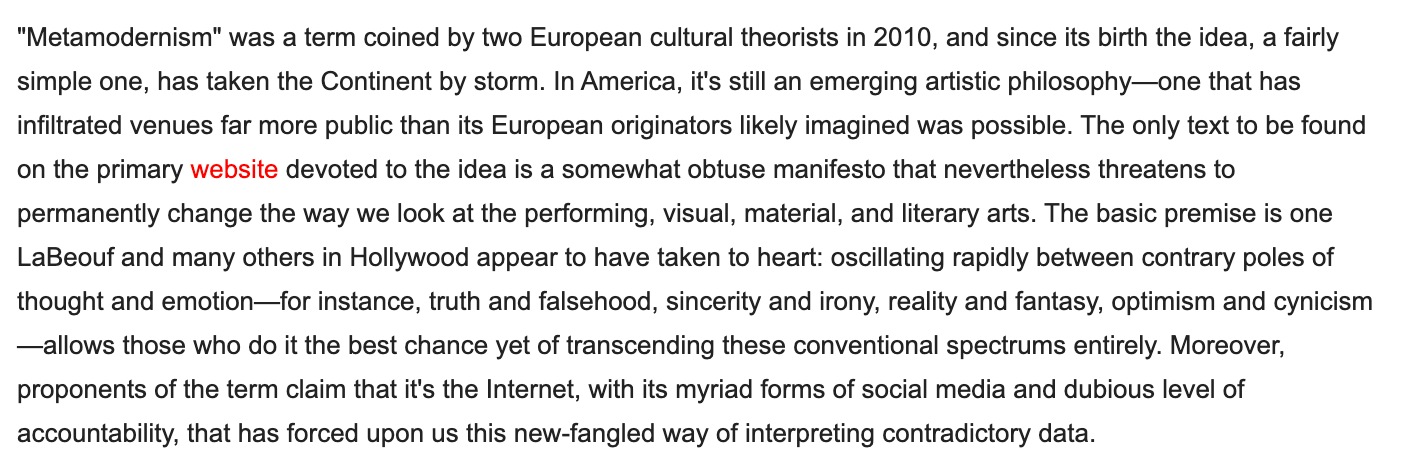

The article prominently linked to a blog-post by obscure British photographer Luke Turner entitled “The Metamodernist Manifesto,” as I deemed the blog-post a useful tool for understanding LaBeouf’s odd use of plagiarism to apologize for plagiariasm:

Less than 24 hours after Indiewire published my essay linking to the “Metamodernist Manifesto”—the only essay then available, in any language, that even arguably defended LaBeouf—LaBeouf linked to the manifesto on his Twitter feed (see above). The day after that (January 12), he tweeted a quote from the manifesto (see above). LaBeouf then deleted that tweet, with his feed consequently looking like this on January 14:

Then a strange thing happened.

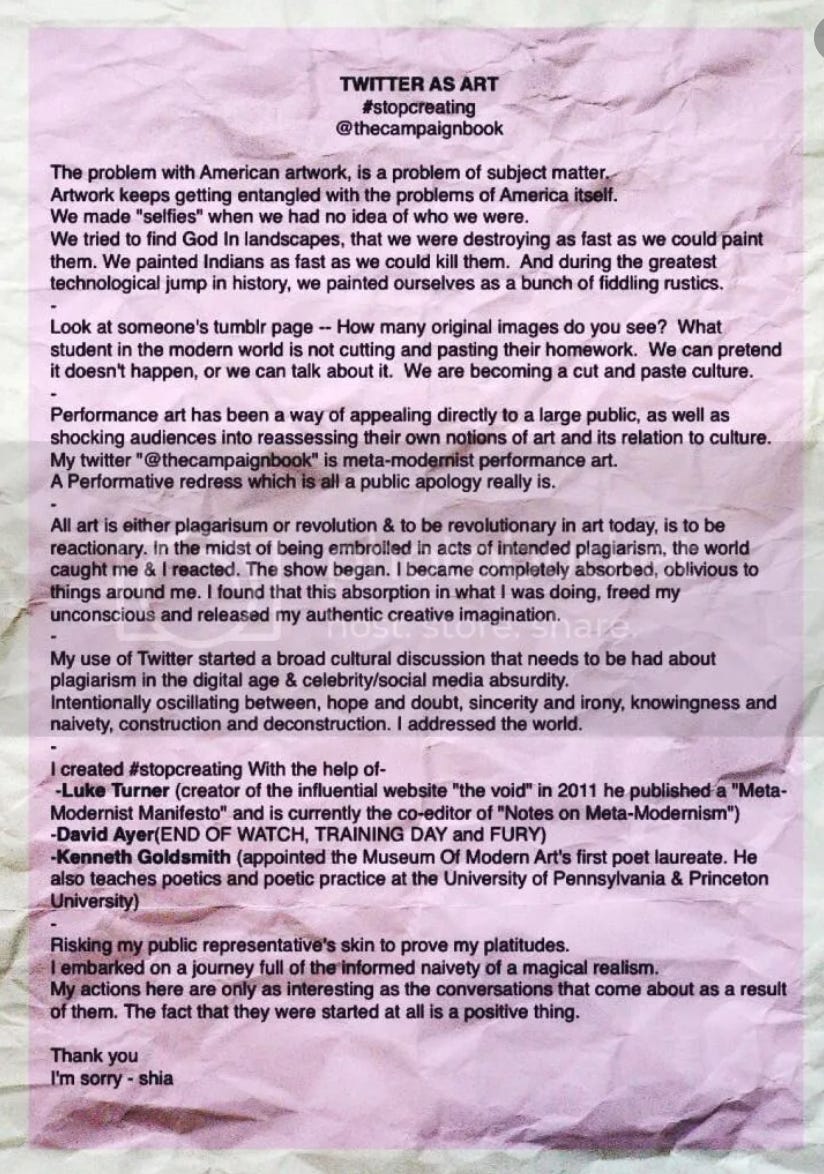

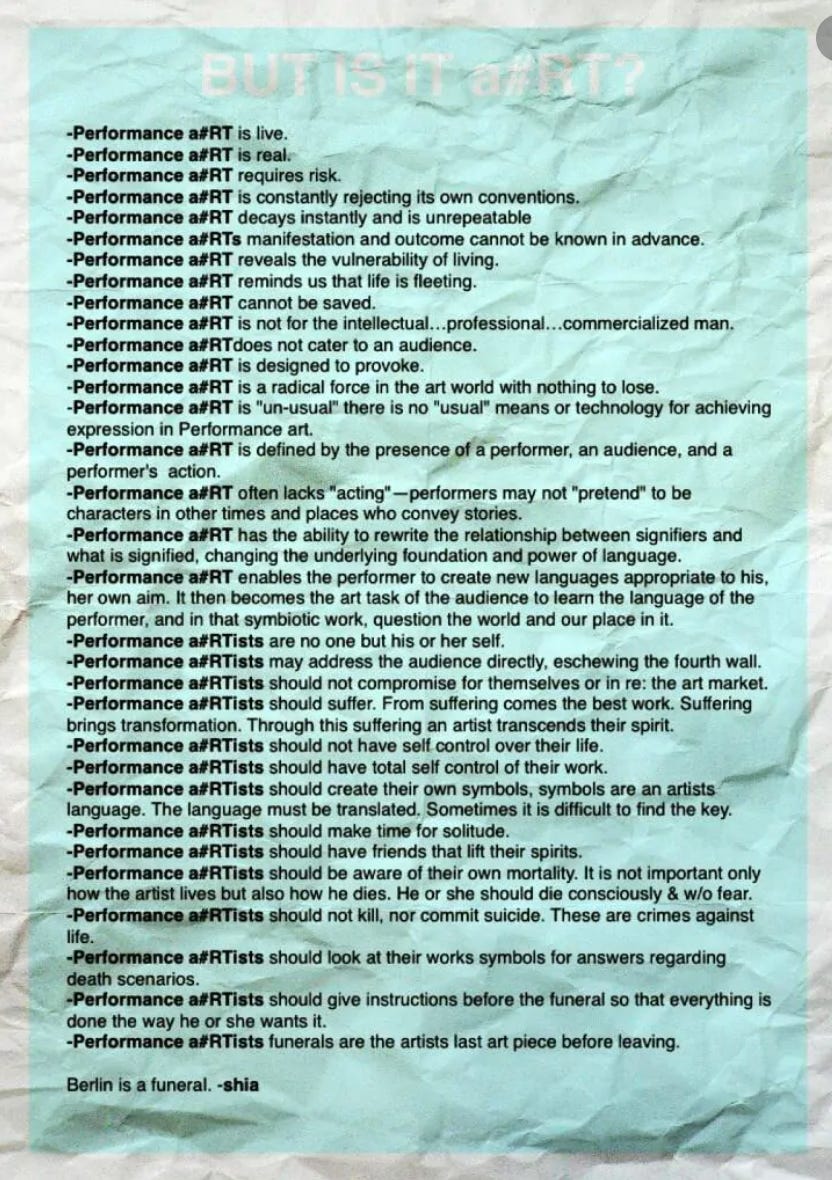

On January 18, just over a week after I’d published my Indiewire article calling LaBeouf a possible metamodernist, he published two manifestos (as images) on his Twitter feed:

In the first of the two manifestos, LaBeouf declared his Twitter feed “meta-modernist performance art” inspired by Turner’s “Metamodernist Manifesto,” at once using a term he’d never before used in his life—in any forum—and then linking to the same document that he’d linked to mere hours after I publicly drew his attention to it.

The course of events was obvious enough: LaBeouf had been at the end of his career; I’d thrown him a lifeline by arguing that he could be considered a metamodernist performance artist, and providing a document substantiating that claim; LaBeouf immediately tweeted out the document, and thereafter wrote a manifesto declaring himself exactly what I’d averred he might be: a metamodernist performance artist.

Within days of my Indiewire article being published, LaBeouf had joined an artist’s collaborative with Turner that the duo called—once they’d added a third member, a friend of Turner’s—LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner.

I knew Turner well, as I’d interacted with him before. Those interactions, nearly all initiated by Turner, had been deeply troubling, but in January 2014 I honestly didn’t know how dangerous Turner was—or realize that his obsession with launching his own stalled career via LaBeouf would see him still harassing me eight years later, lying to Columbia Journalism Review about events I detail (with proof) in Part II of this essay.

Nor could I ever have imagined that a media outlet like CJR—long a self-appointed watchdog over contemporary media—would provide me with the clearest example imaginable of the moral, ethical, and professional bankruptcy of so many in today’s institutionalized media. In Part II of this essay I introduce my interactions with Luke Turner and CJR, a series of events that gets stranger than you would ever imagine.

Enjoyed reading this.. and I got a chuckle at my own thought that Roger Stone himself might be: a metamodernist performance artist.... thanks for your help keeping our democracy!

Reading Shia's copy and paste theory, makes me think of the word *citation* and the need to insert in the appropriate places/styles. My understanding of University material is the students first need to learn the history of their majors and display understanding it through repeating it (with said citations) and connecting it with subject of the paper being written per the profs wishes. Copy and pasting is lazy, cheating, and wrong. What does anyone learn doing that in the end? I get it. University comes at people hard, fast, and with volumes of work to learn in a short period of time. Double overload is even harder, faster, and more volumes of work to get in the head, but no one said people have to take a full load of classes. Take three if that is more the speed you want to work at. I could not read all of Shia's words, but I forced myself to skim them and my conclusion is bullshit homework handed in, in an attempt to fake the way through it.