Substack Essay Series #3: The Strange Story of Me, Shia LaBeouf, and the War Between Old Media and New Media (Part III)

For reasons I still don't understand, Columbia Journalism Review recently published a passel of lies about me and LaBeouf. In this personal essay, I set the record straight.

{Note: This is Part III of a multi-part essay on the ongoing debate between major media and independent journalists working on Substack about whether the former is confirmably more reliable. Part I of this essay is here; Part II is here; Part IV is here; and a coda is here.}

CJR (Part 3)

I’m going to take a brief detour from my story about Shia LaBeouf and his artistic collaborator Luke Turner to give a little more information about my harrowing experience with Columbia Journalism Review (CJR), a self-appointed major-media watchdog which, from my personal knowledge and experience, has the most broken, dishonest, indeed profoundly grotesque “fact-checking” process I’ve ever encountered at any media outlet—and I’ve been in journalism for 27 years, written for more than a dozen major media outlets, taught journalism at a major public research university for six years, and been in contact with countless fact-checkers for media organizations over the last quarter-century. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen anything remotely like what I encountered at Columbia Journalism Review in 2021.

In addition to teaching my journalism students at University of New Hampshire the four core principles of journalistic writing, research, communications, and ethical practices—namely, “objectivity,” “accuracy,” “transparency,” and “honesty,” principles collectively known as the “OATH” principles—I teach them that the last two of these principles require that a journalist be willing to issue corrections when they make a mistake, but also try to avoid corrections on the front end by checking in with their sources when two sources conflict.

If a journalist does, instead, what CJR apparently encouraged its contributing writer Lyz Lenz to do—get a quote, see it contradicted by a second source, and then never check back with your first source—you’re virtually assured of publishing falsehoods, and potentially defamatory ones. Not returning to a source is particularly unethical when (a) you’ve assured the source multiple times that you will do so, as was the case with Lenz and me back in the late fall of 2020, (b) your source only declined to provide emails to protect individuals whom you as the journalist have since decided (with the consent of such individuals) to bring into your story, thereby rendering your source’s initial refusal to provide such emails moot and necessary to revisit, and (c) the source has already told you that proof of everything he has said does in fact exist and he is in fact in possession of it.

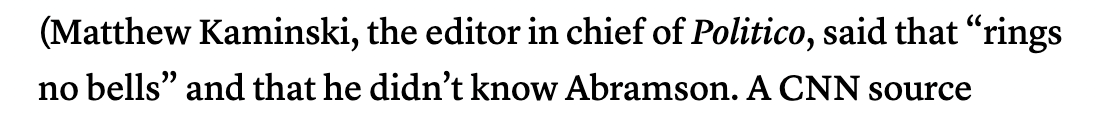

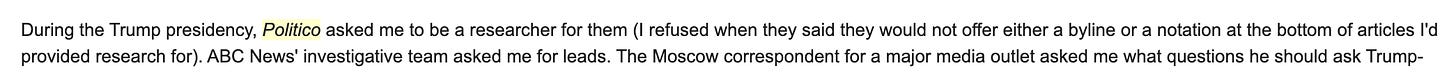

So, for instance, when a source tells you on the phone that in 2017 he spoke repeatedly with a Senior Investigative Reporter at Politico about stories involving the Trump administration (see Part IV of this essay for more), and was subsequently asked to provide research to Politico for free without attribution, you don’t contact a Politico editor who arrived at the outlet years later, in April 2019, to ask him if he ever offered your source a paid “job.” And when your source thereafter provides proof of his claims (see below), you don’t refuse to run them when you know your readership believes your source lied about ever being in contact with Politico in the first place. Here, then, is what Lenz wrote about me and Politico:

Excerpt 1

Excerpt 2

Here’s what I actually told Lenz about my 2017 contacts with Josh Meyer, then the Senior Investigative Reporter at Politico:

Excerpt 3

If Lenz had confusion about what year this occurred, or about who I’d spoken to at Politico, or about whether doing research for Politico meant getting paid by them or having a “job” with them (which it did not, as I think I pretty well indicated to Lenz by saying the digital media outlet was not offering even “a byline or a notation at the bottom of article” for my work), Lenz had an easy fix: she’d already told me on the phone that she would get back to me if she needed any clarifications. Instead, she sought the aid of Meyer himself, who—believing Lenz’s “report” that I said I’d been offered a “job” by Politico—came onto her Twitter feed to deny that. It was pointless, of course, as I agreed with him: Politico had never offered me paid employment.

But what Meyer was really angry about, I think, as Part IV of this essay confirms, is that he had put down in writing how desperately he needed my aid in doing the job he was paid for.

{Note: Lenz knew I was an avid record-keeper and had proof of everything I’d told her, as even my email to her in part about Politico included three screenshots confirming something else I’d noted in the email—that my Twitter feed was followed by members of the incoming Biden administration. In fact, one of the three screenshots was proof of my claim that the National Security Advisor of the United States, Jake Sullivan, had followed me minutes after being named to his post—something Lenz made sure not to include in her article because it was surprising, it bolstered my credibility, and she had documentary proof of it that she would have had to acknowledge. Ironically, Lenz had commented, via email, on the amazing thoroughness of my record-keeping, despite thereafter writing a piece that called into question whether I could prove anything I’d said to her.}

Luke Turner (Part 2)

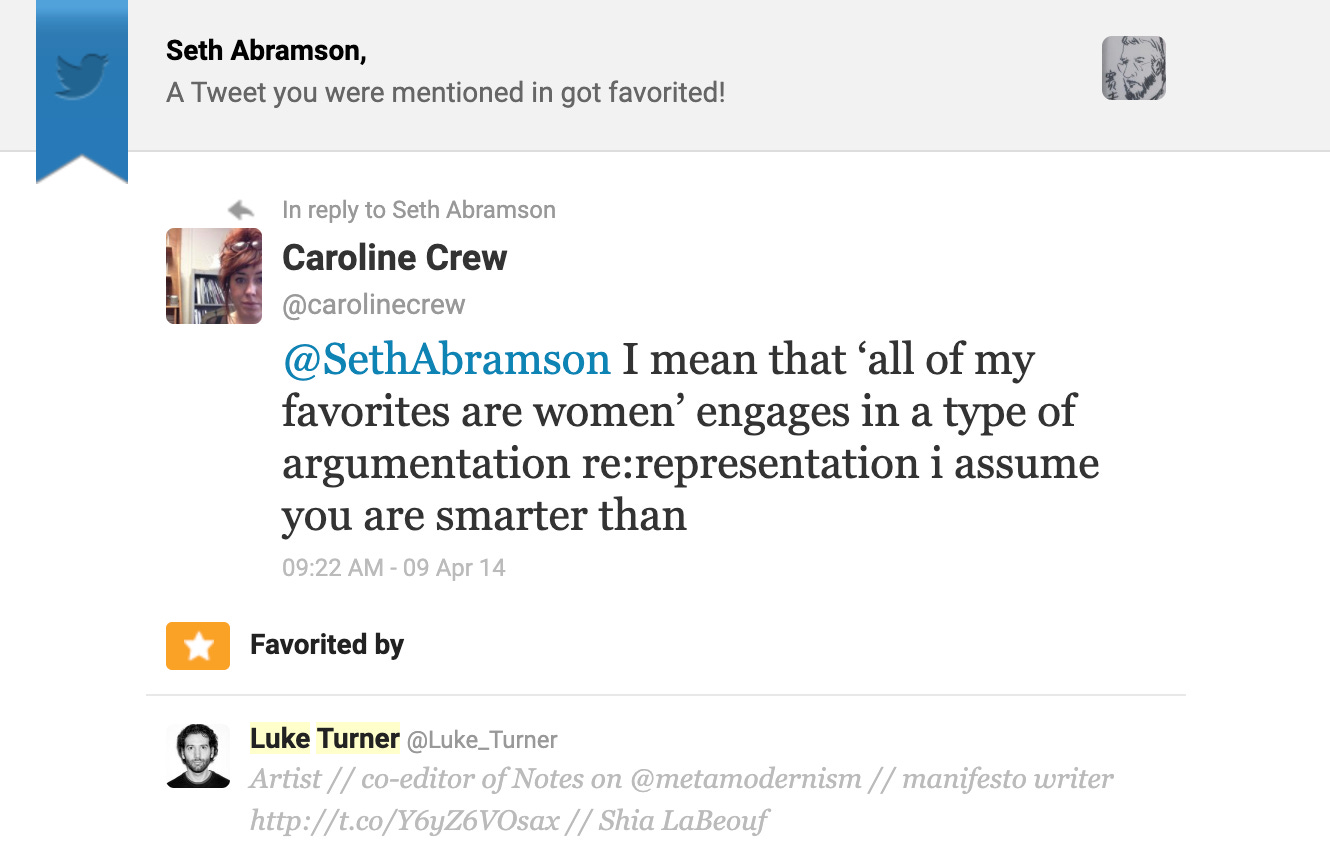

I mentioned in the last part of this essay that Luke Turner’s tone toward me changed in the spring of 2014, as I continued writing about metamodernism in major media publications—and to a fairly large readership, Lenz’s subsequent claims about the size of the Indiewire and Huffington Post audiences notwithstanding—and Turner continued working on art projects with Shia LaBeouf. Where previously Turner had showed up whenever I said a word (“metamodernism”) he considered himself the owner of, now he was showing up in conversations I was having online with third parties who didn’t even know who Turner was:

I should have seen the warning signs in this behavior, but I did not.

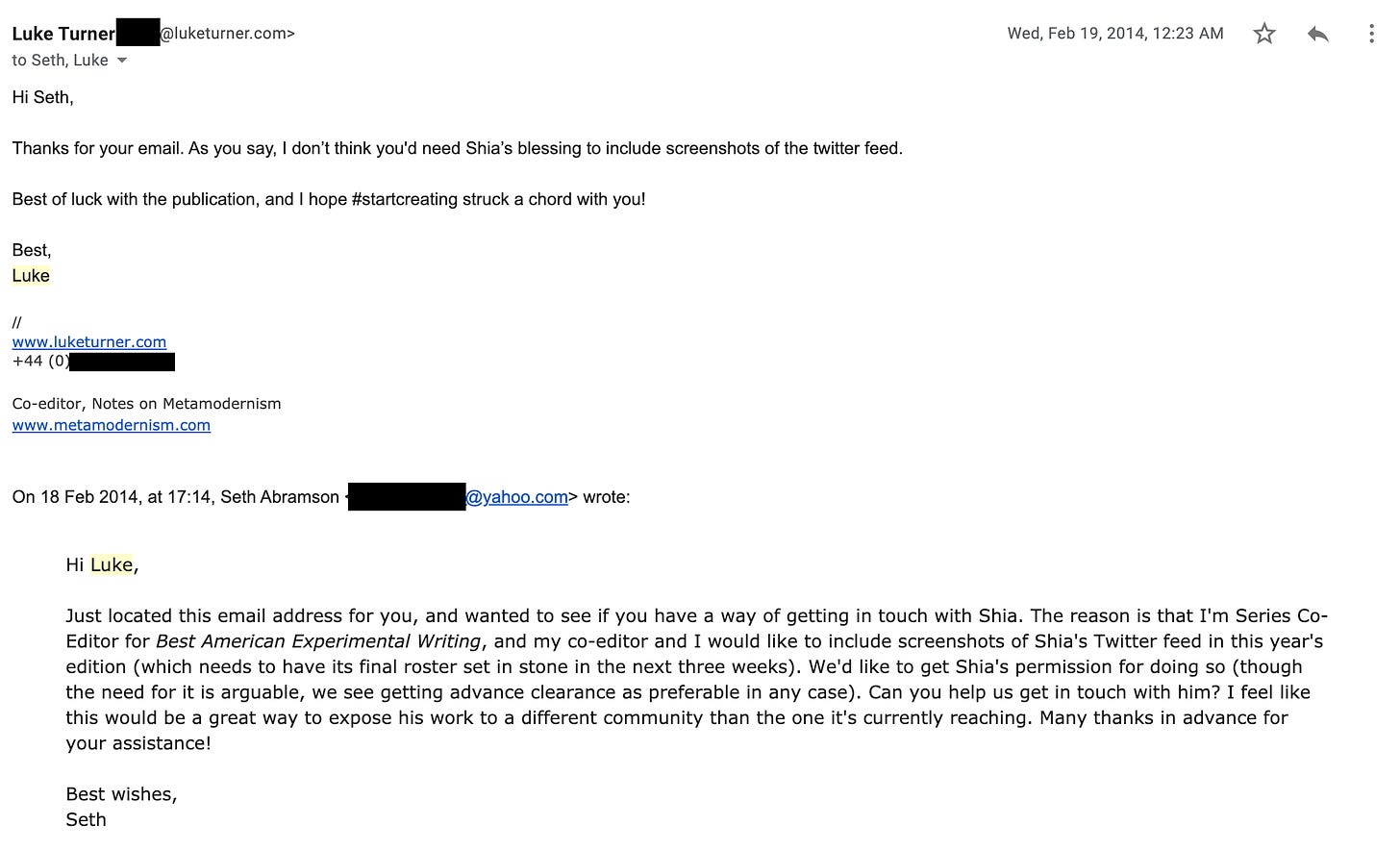

Instead, because Turner was the then-webmaster of much of LaBeouf’s social media presence, and because the university press-published, non-profit annual anthology of experimental writing I co-edited with Damiani wanted to publish, as part of a free online feature, screenshots of LaBeouf’s Twitter feed (which Turner was taking credit for as part of the #IAMSORRY performance-art piece being touted by the LaBeouf, Turner & Rönkkö collaborative) I wrote Turner as part of an effort to get permission to use the screenshots. It was a form of permission I knew, as an attorney, we didn’t actually need—given that we were not charging any money for the screenshots and that they merely sought to honor LaBeouf—but I was trying to be courteous.

I should have realized by then that Turner would under no circumstances want me to be in touch with LaBeouf, but it didn’t really occur to me because I had no real interest in being in touch with LaBeouf, anyway—and frankly agreed with Turner’s view that LaBeouf’s permission wasn’t needed to honor his work via a profit-free screenshot of his public and notorious Twitter feed.

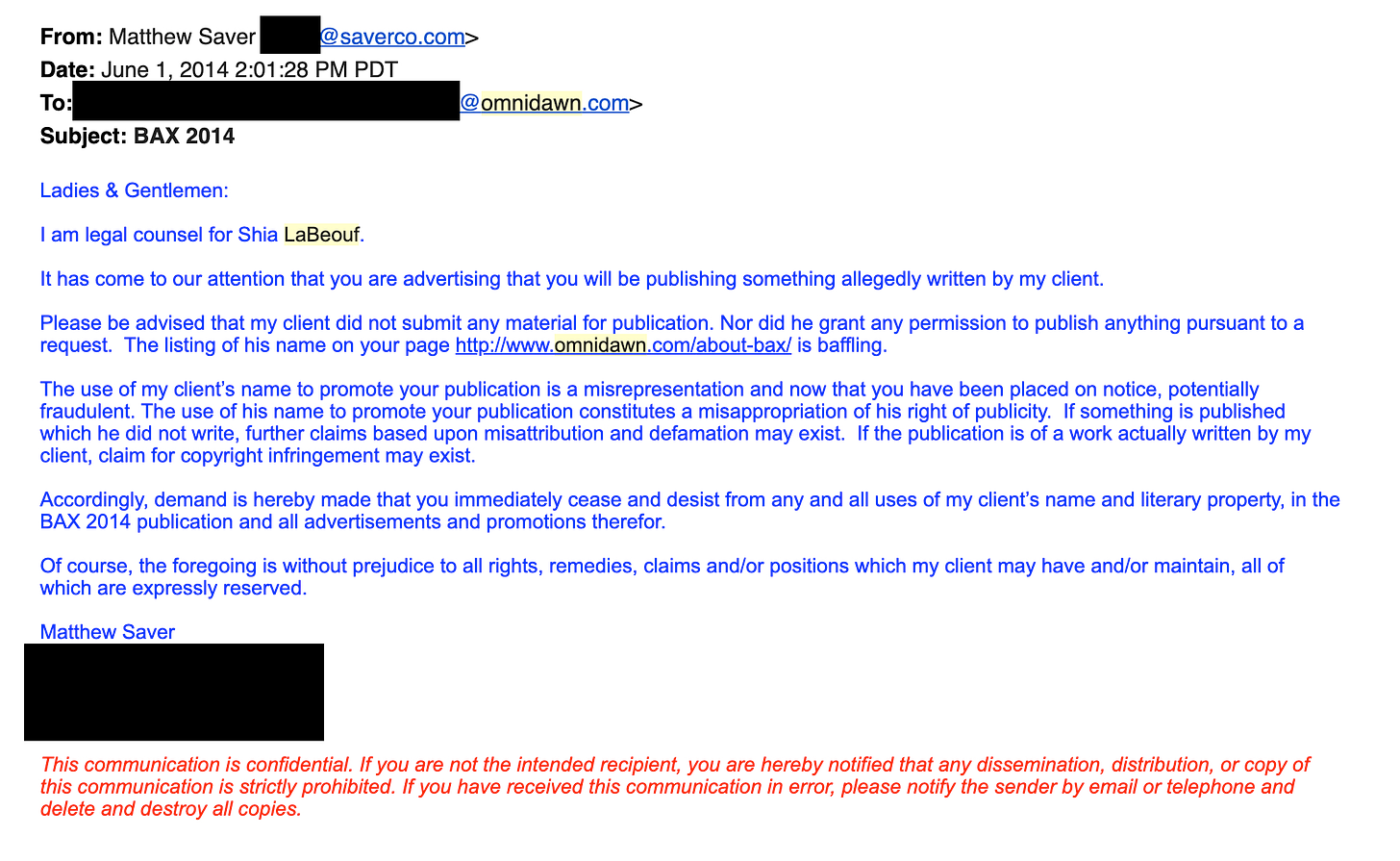

Then, like a bolt from the blue, I received a positively bizarre missive:

My publisher and co-editor were flabbergasted. What did Matthew Saver mean in saying that we were “publishing something allegedly written by my client”? Surely he wasn’t contesting that LaBeouf was the author of his own Twitter feed—the only work by LaBeouf we’d ever contemplated publishing? We were thrown for such a loop (after immediately deciding, of course, that we would under no circumstances use material from LaBeouf on our non-profit website seeking to honor, among the work of many other artists, his work) that it took me days to figure out what Saver was talking about.

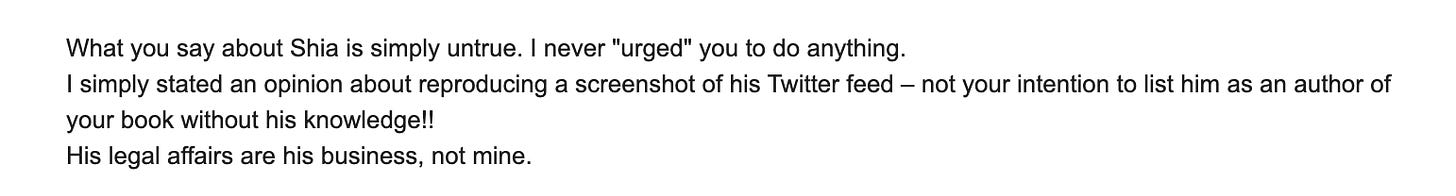

Ultimately, about two weeks after receiving Saver’s email, I wrote Luke Turner seeking answers on why I was getting a cease-and-desist letter from LaBeouf’s attorney. Here was Turner’s response, in relevant part:

I had never written anyone, or ever expressed any sentiment publicly or privately, that involved “list[ing] [LaBeouf] as an author of” the anthology I edited—which of course didn’t even have an “author,” as it was, again, an anthology of works by 75 writers. More to the point, LaBeouf wasn’t going to be in the anthology, as he’d been selected for a free, non-profit online website. It soon became clear that Turner had gone to LaBeouf to try to gin up a lawsuit against me as a means of driving a wedge between LaBeouf and me—words I type now with some amusement, as I had never sought any sort of relationship with Shia LaBeouf in 2013 or 2014, and haven’t sought one since.

So by June 2014 I found myself in the preposterous position of having received a cease-and-desist order from a man I’d never met, simply because an obscure British artist whose career I’d effectively made by directing a Hollywood mega-star in his direction was needlessly territorial about (a) the said mega-star, and (b) an abstract concept that has been in academic circulation since before the said obscure British artist was born.

I felt, in short, that my life had become stupidly ridiculous.

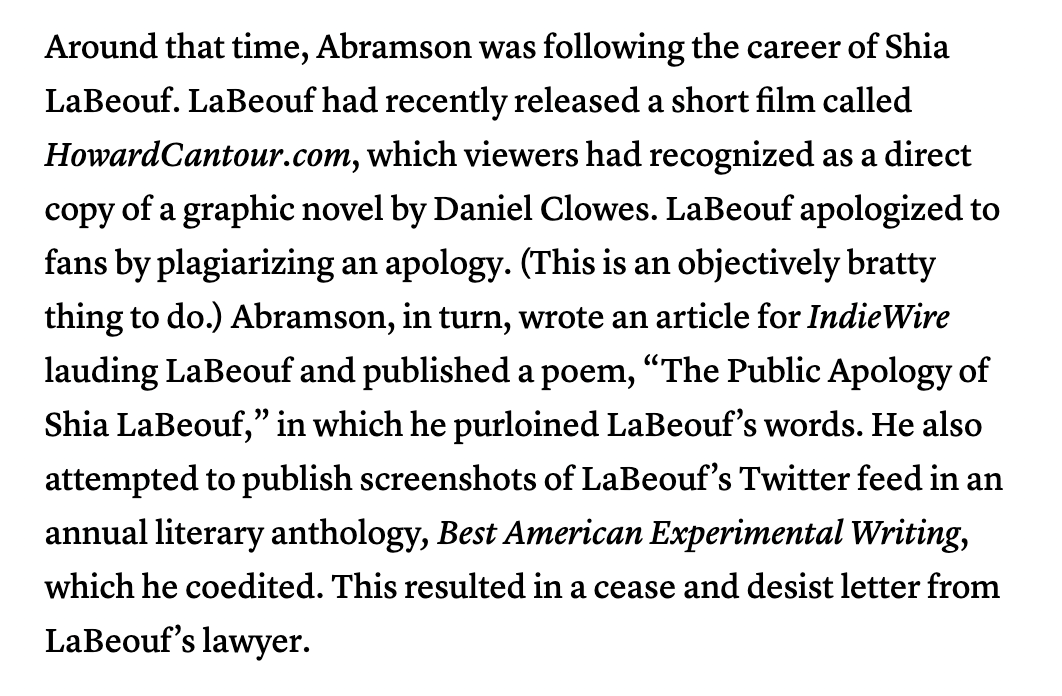

What I didn’t imagine, when I told the story offhandedly to CJR as part of an hours-long conversation, was that it would end up being written up in the way it was—a way that bore little similarity to anything I’d discussed with Lenz. Indeed, the parts she got right were chiefly those she Googled. Here’s the beginning of her treatment of the saga:

Everything here is wrong. I was in no way a “follow[er]” of LaBeouf’s career in 2013; his plagiarism scandal was big news in late 2013, and I noted it along with everyone else. Indeed, I had no particular opinion on LaBeouf at the time, becoming interested in his scandal only because I was writing a column on metamodernism for Indiewire, and LaBeouf’s actions at the tail end of the scandal seemed, to me, metamodernist in bent—if only accidentally.

My article on LaBeouf did not “laud” LaBeouf, as anyone who read it would know. The poem Lenz references was indeed published online on January 13, 2014, and later on in my 2015 book Metamericana, but it did not “purloin” (i.e., steal) Shia LaBeouf’s words. In fact, the poem was preceded by a statement that read, “Author’s Note: The poem ‘The Public Apology of Shia LaBeouf’ comprises a collage of 40 discrete dependent and independent clauses tweeted (not retweeted) by actor Shia LaBeouf from December 13, 2013 to January 13, 2014. Punctuation and typeface has on occasion been amended.” No artist or journalist would ever say in such a situation—when the citation precedes the usage—that words have been stolen.

But Lenz was just getting warmed up. Here’s the second part of her “special report” (the term CJR used to advertise her article) on my brief involvement with Turner and LaBeouf:

It took me a while to make heads or tails of this. Obviously my correspondence with Turner began half a year before Turner first spoke to LaBeouf, and as Turner has conceded via email, I was the very reason he spoke to LaBeouf in the first place—in January of 2014—so Lenz’s claim, which she falsely attributes to me, that I began corresponding with Turner after he’d already begun working with LaBeouf is bizarre.

Just so, my statement about being “the reason Shia LaBeouf became a performance artist” was based on the words of both LaBeouf himself (on Twitter) and Turner (via email), and had nothing to do with the three-person art collaborative LaBeouf and Turner had thereafter formed with Nastja Säde Rönkkö. I never claimed any influence, nor would I ever claim any influence, on the artworks of LaBeouf, Turner & Rönkkö.

I don’t know how to take LaBeouf’s claim that I was using his name to sell copies of a print anthology he wasn’t in, nor his apparent continued insistence that I wanted to make him a co-author of a book with precisely zero authors that (again) he wasn’t a part of. But if these bizarre statements by LaBeouf and Turner surprised Lenz, as they were inconsistent with anything I’d said to her, she made sure not to contact me—as she’d promised—for comment, correction, or clarification.

Instead, she invented some new information from whole cloth.

Having never said to Lenz that I remained a “fan” of LaBeouf’s after his recent sexual battery scandal—which is still ongoing—Lenz invented the notion that I felt otherwise by linking to a tweet of mine from six months before the LaBeouf-FKA Twigs scandal hit the media. In doing so, and in writing up her own sleight-of-hand as “allegations of abuse were brought against LaBeouf…Still, despite everything, Abramson remains a fan”, Lenz gave the impression that I was unfazed by domestic violence. For personal reasons I won’t get into in this essay, this lie in particular was traumatic for me.

When CJR was contacted with the evidence above, and thereafter asked to correct Lenz’s misstatements—misstatements that accused an attorney of theft, a professor of celebrating and even practicing plagiarism, an editor of having no editorial standards, and someone who knows something about domestic violence about being an apologist for it—I was told, in slightly prettier language, to go fuck myself.

I was told this by the Managing Editor for CJR, Betsy Morais, and by Stuart Karle, the former adjunct faculty member at Columbia University who was, inexplicably, retained to represent Columbia University in this matter.

And then it got worse.

Part IV of this essay includes the conclusion of this bizarre story about the collapse of fact-checking at major-media institutions in the United States.

It gets WORSE? This is an absolute nightmare for you, Seth! :(