Substack Essay Series #5: The Strange Story of Me, Shia LaBeouf, and the War Between Old Media and New Media (Coda)

An unexpected epilogue to my strange-but-true story of trying to navigate the battle between American journalism's past and its future. Strap in—this one gets a bit wild.

{Note: This is the final part of a five-part essay on the ongoing debate between major media and independent journalists working on Substack about whether the former is confirmably more reliable than the latter. Part I is here; Part II is here; Part III is here; and Part IV is here.}

Introduction

I didn’t think I’d write a coda to this essay series. I certainly had no plans to do so.

But then a thing happened, and then another thing happened, and finally a third thing happened that helped me see a larger picture in what I’d previously written about only in piecemeal: something more than just an ongoing tilt between Old and New Media.

What I thought I had glimpsed, following these three unexpected events, was a crack in the very foundations of American journalism.

To be clear, I don’t flatter myself to think I’ve seen much more than the barest glimpse of this weakened foundation, but I do think I’ve glimpsed it, slantwise at least. And if telling this story in a way that is uncomfortable for me and might even run the risk of looking self-aggrandizing or gauche is in any way helpful to exposing that weakened foundation, shouldn’t I do it? Whether I should or shouldn’t feel this way, I do feel I owe an unpaid debt to journalism—a communications, research, writing, and ethical practice I’ve now been committed to for 27 years, and that I teach at a large university to what I hope will be a new generation of courageous independent digital journalists.

It’s with all the foregoing in mind that I hope you’ll indulge me in publishing one more piece of my strange story about Shia LaBeouf, Columbia Journalism Review, and a now-disgraced freelance journalist, Lyz Lenz, who just a few days after getting fired from the Cedar Rapids Gazette for being too biased to produce competent journalism was unleashed on me—brutally—by one of the nation’s largest and richest universities in conjunction with one of the nation’s oldest and most once-respected media watchdogs.

This coda begins with the Kremlin—a fact that seems as humorously “on-point” to me as it does, I would guess, to you.

The Kremlin and a Second-Tier Humor Website

If anything can happen to a so-called “Special Report” that an Old Media watchdog has contracted for that confirms it, thereafter, as being neither a report nor special, it’s to have that document picked up by the Kremlin for use as anti-American propaganda.

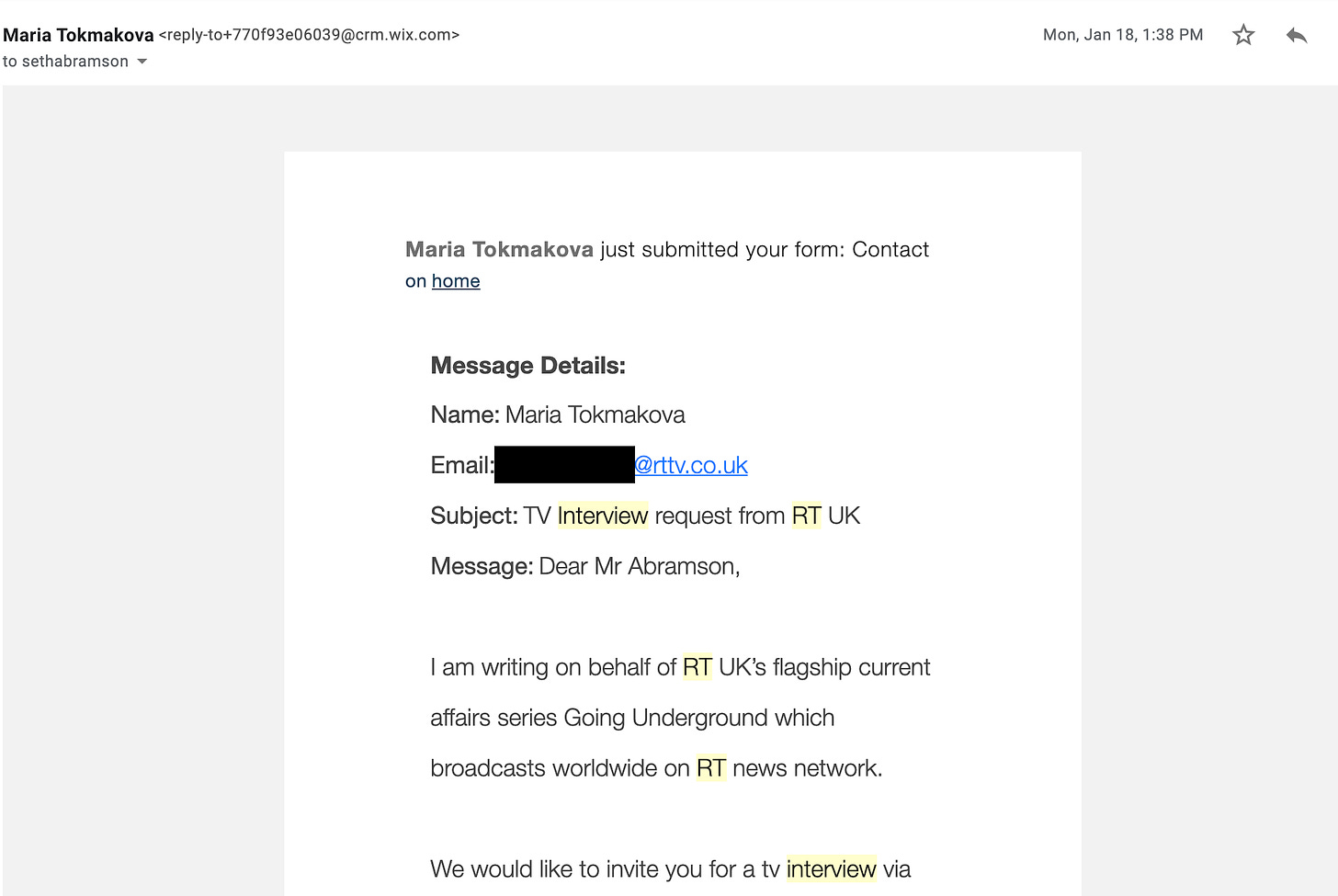

Because I have been a very public critic of Donald Trump since the middle of 2015, the Kremlin’s propaganda arm (Russia Today, popularly known and advertised as RT) has been obsessed with me for years now. Three times RT has tried to interview me—most recently, just a few weeks ago, in January—and three times I’ve declined the invitation, twice without sending any response and once by sending a brusque declination. Here’s their most recent approach, which I ignored:

In lieu of speaking with me, the Kremlin settles for writing hit-pieces about me, or at least has done since I first turned it down for an interview in 2017.

As the years wear on, the number of derogatory references to me by RT has mounted. Google News returns ten RT articles referencing me—almost always negatively, with one or two neutral references thrown in for good measure—but the total number of RT articles attacking my credibility since late 2015 would probably be closer to twenty.

So when Lyz Lenz published a now-conclusively-debunked hit-piece about me, the Kremlin couldn’t resist hopping aboard. Indeed, it ran a televised segment about me that more or less just lifted Lenz’s words wholesale, in some cases reading them directly off a teleprompter. And then the bizarre Kremlin creature who acted as the congenial, English-speaking face of this single-use propaganda package wrote me on Twitter to try to heckle me and draw me into a discussion. It was eerie and morally bankrupt and candidly a little bit sad, which is generally how I think of the Kremlin.

How must Columbia Journalism Review feel to know that its dishonest hit-piece on a longtime Trump critic weas quickly mainlined into the veins of propagandists from a government entity the FBI now confirms tried to interfere in a second general election in the United States in the last five years? {Note: This is a rhetorical question, of course. Like any dying media entity, CJR hunts for clicks howsoever and wherever it can find them.}

More to the point, given that the CJR article in question persistently and unabashedly repeated Kremlin propaganda—even citing disgraced media outlet The Hill, which spread such propaganda on the subject of the Trump-Russia scandal (via Trump agent John Solomon) during the 2020 primaries and general election—one wonders if, now that this parroting has been clocked by Putin’s autocratic superstructure, CJR still feels pride in standing by, specifically, Lenz’s parroting of Kremlin talking points?

This is not an academic question. Indeed, among the many items that the Kremlin and Lenz agree on (all quotes hereafter by Lenz herself) are these:

America in 2016 was not “manipulated by sinister outside forces [including] Russia”, it merely “voted for a racist misogynist.”

To the extent Russia had any involvement in the 2016 election, it was exclusively “Russian organized crime”, so only “experts on Russian organized crime” should ever have been writing about Russia’s role in the 2016 general election.

The Mueller Report found “no lawbreaking, only a lot of shady dealings with a lot of shady men” (presumably these “shady men” were from the Russian mafia, not from Russian intelligence or any other Kremlin assets, agents, or entities).

Of Trump campaign collusion with Russia—for instance, Trump’s campaign manager Paul Manafort giving proprietary campaign data to a confirmed Russian intelligence operative during the general election, which fact has been confirmed by the Mueller Report, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence report, and hundreds of major-media articles—Lenz writes, quoting a source, “What we know is that there was a crazy amount of disturbing contact, interaction, and [a] kind of mutual affection—or admiration—between the Kremlin and the Trump campaign. And that is it.”

The fact, established by both Mueller and the Senate, that there was—at a bare minimum—2016 collusion between the Trump campaign and Russian nationals that cannot be proven as criminal beyond a reasonable doubt, is, in fact, just a “narrative that doesn’t hold up.”

To Lyz Lenz, the view that Trump was secretly working on a major real estate deal with the Kremlin during the 2016 presidential election—as his attorney, Michael Cohen, the Mueller Report and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence confirm—is simply fueled by “a desire to believe that America is controlled by a nefarious foreign power”, even though “the evidence just isn’t there” for any involvement of the Russians in our elections or campaigns other than some benign “contact, interaction, and mutual affection” between certain U.S. and Russian nationals.

“The reliability of the Steele dossier is, to put it mildly, in question…[the dossier is] dubious, unvetted, and shady as hell” (Lenz here links to The Hill). Per Lenz, virtually no part of the dossier is accurate, despite many months of major-media reporting to the contrary.

These are just a few choice quotes from Lenz’s article. In general, the recently fired freelancer repeatedly claims to have a better understanding of the most complex federal criminal investigation of our era—up until the January 6 investigation, at least—than an author who wrote three national bestsellers on that very topic. This said, I wouldn’t have written a coda to my earlier essay simply because Lenz’s supplanting of her own ignorance on the Trump-Russia scandal for my knowledge of it, in an article betraying no familiarity with my writing on the subject, was later deemed useful by the Kremlin. As I said, the Kremlin has been looking for ways to discredit me for a while now, though I’m at best a minor gnat in their ointment and hardly worth the trouble.

No, I write this coda for a different reason.

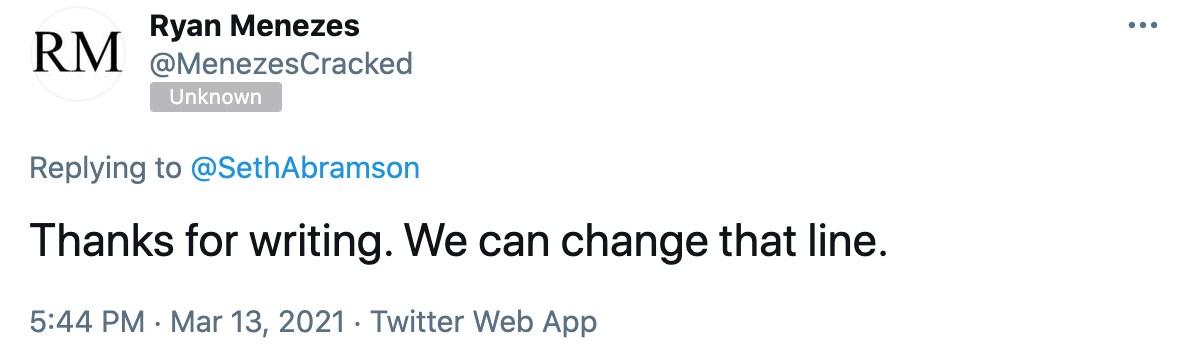

I write this because it wasn’t just the Kremlin that found Lenz’s work to be useful to it. A humor website, Cracked, assumed that the things Lenz had written were true, and saw some comedic value in quoting her work. And so it did so, hoping my comments about CNN and LaBeouf would gets some laughs from Cracked readers, who certainly don’t go to that site looking for journalism of any variety or even anything particularly accurate. Nevertheless, when I saw that a humor website had twice called “false” my claims about CNN and LaBeouf that were, as this essay series confirms, accurate, and when I saw that Cracked had linked to Lenz’s article as its proof that my statements had been false, I decided to write the author of the Cracked article, Ryan Menezes.

I sent Menezes a link to this essay series and told him—in strong terms—his article needed to be “fix[ed].” Here’s what he sent back, in a period of time not much longer than it would take to read the essay series to which I had just directed his attention:

And so they did.

They fixed their mistake—and did it quietly and immediately and without any needless back-and-forth.

After having just spent weeks getting berated by CJR representative Stuart Karle—and told that everything in CJR’s “Special Report” on me was not, in fact, a report at all but mere “opinion”—and having heard from CJR justifications for not making corrections the likes of which I’d never before encountered at any journalistic institution, here was a humor site instantly retracting a false claim the moment it saw proof it had made one.

How messed up is American journalism when a self-declared scion of major-media oversight is getting parroted by Kremlin propagandists known to be inveterate liars, even as a second-tier humor site—in dealing with the very same subject and very same information—exhibits consummate professionalism? The answer: pretty damn broken.

I have many stories along these lines from the past few years that I could tell here, but again, this essay series was originally intended to focus on the ongoing brouhaha between a few major-media types (and academics like Jay Rosen and Sarah Roberts) and political “substackers” like Matt Taibbi and Glenn Greenwald. I used “my story” because I thought it fit the theme, not because Proof is a repository for war stories.

This said, just as I was making the decision to write this coda, something felicitous happened: I had an exchange on Twitter that was a perfect fit for this article. Like any writer, I decided not to pass up the opportunity to share an on-point anecdote that had serendipitously showed up on my doorstep. This one involves in primary part a cable-news employee, but to really make the point the story had to be expanded somewhat—remember, my life has been strange these past few years, and my war stories therefore likewise—to include Michael Cohen, Rachel Maddow, and the President of MSNBC.

Kyle Griffin, the President of MSNBC, Rachel Maddow, and Donald Trump’s Fixer

I’ve been reading Kyle Griffin’s Twitter feed for years now. Griffin works at MSNBC, and is one of the best news aggregators out there—news aggregation being a genre of journalism that broadly falls under the heading of “metajournalism,” and is adjacent to (but different from, in many key respects) the curatorial journalism I myself practice. In all the years I’ve been following and retweeting Griffin, he’s never responded to me or in any way referenced me, so I was certainly surprised when he suddenly did on March 16. The interaction wasn’t what I expected, either; I realized shortly afterwards that a brief description of it belonged in this coda on battles between Old and New Media.

Some background useful to this story: I’ve spent 36 of my 44 years shuttling between the State of New Hampshire and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. I attended what was at the time the only “R1” (“Very High Research Activity”) college in the former state, Dartmouth College; I practiced law for years as a trial attorney with the Nashua Trial Unit of the New Hampshire Public Defender; I now teach journalism, pre-law, and other subjects at the Granite State’s second-ever R1 school, University of New Hampshire; for what it’s worth—which may be nothing, but it adds some color to this story—I have more followers on Twitter than any resident of New Hampshire, and I write mainly about politics on Twitter; I’ve taught multiple students who now serve in the New Hampshire House of Representatives; a work colleague who is a friend of mine is among the top political experts in the state. In other words, I’ve a good claim to be generally knowledgeable when it comes to politics in New Hampshire and New Hampshire generally. Even growing up in Massachusetts in the 1980s, my family lived near the New Hampshire border—my father worked in New Hampshire, for Digital Equipment Corporation, then one of the major employers in the state—so I always felt close to the Commonwealth’s neighbor to the north, even before I lived there and was a radio DJ there and cohabited with a fiancée there and voted there and had some of the most formative years of my life there. And I live there now, and have since 2015.

So if there’s one thing I know about New Hampshire, it’s that it was a GOP-leaning state in national elections in the last century, but has been firmly “blue” in this one.

The last time New Hampshire voted for a Republican presidential candidate was over two decades ago, in 2000. Both of our U.S. senators are Democrats; both of our U.S. representatives are Democrats; and it’s been that way for some time. At the national level, we are a “blue” state and pretty clearly so. This is simply indisputable.

So I was taken aback when Griffin, an MSNBC employee, tweeted out an article from the Washington Post that was unambiguously about national politics (“Biden and Allies Launch Stimulus Campaign Focused on Competitive Battleground States”), and in doing so did something I hadn’t seen anyone do since I was living in Nashua between 2001 and 2007: refer to the State of New Hampshire as “GOP-leaning” at the national level.

I knew Griffin was wrong, so I quote-tweeted his tweet to amplify the Washington Post article, a good one, while noting that the classification of New Hampshire as a “GOP-leaning” battleground state was wrong. Maybe my tweet had a hint of snark in it, but frankly it was pretty milquetoast in Twitter terms.

For some reason, Griffin decided to respond to me, having never before done so despite me putting hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of retweets of him, and quote-tweets of him, on my feed over the last five-plus years. Here’s what he wrote:

Both chambers of the state legislature are controlled by Republicans. The governor is Republican. [Senator] Maggie Hassan (D) only won her Senate seat by about a thousand votes.

There was nothing offensive about this reply whatsoever, it was just… sort of odd.

Griffin had unambiguously written that the State of New Hampshire was and is a “GOP-leaning [battleground state]” in national elections, and he was wrong, and after being pretty mildly called out on the error—not just by me, but by others responding to his tweet, who noted also that his characterization didn’t fit the State of Nevada, either (he’d also called Nevada “GOP-leaning” at the national level)—his response was to (a) change the subject to state-level politics, and (b) allege that a Democrat narrowly winning an election in the Granite State meant the state was actually “GOP-leaning.”

So I engaged with Griffin again, noting that my home state’s entire Congressional delegation is Democratic and has been for some time, and that my home state has reliably voted for the Democratic presidential candidate for many election cycles now, and therefore my state can’t under any circumstances be called “GOP-leaning.” I noted also that, like many New England states, we have a slightly different profile at the state level than we do in our national elections (the subject of the Washington Post article Griffin linked to). For instance, like New Hampshire, both Massachusetts and the State of Vermont have Republican governors but are reliably “blue” states that would never be called “GOP-leaning.” Just so, another New England state, the State of Connecticut, had a Republican governor for sixteen years straight between the 1990s and 2010s, but was a reliably “blue” state in federal elections the whole time; likewise, the State of Maine had a GOP governor from early 2011 through early 2019, and was similarly considered a “blue” state the whole time. Anyone who, like me, is a lifelong New Englander knows that you can’t discuss federal voting in New England states interchangeably with state voting. Those are two very different conversations.

In any case, when I pointed this out to the MSNBC journalist who’d falsely called New Hampshire a “GOP-leaning” state, here’s what he wrote me:

Your opinion has been registered. Thank you. I will keep the tweet and characterization as is. Have a good night.

Certainly, readers of Proof can note the tone here just as well as I can. It doesn’t take being a university professor who teaches tone—as I do, in both my “Professional & Technical Writing” course and my “Advanced Professional & Technical Writing” course at UNH—to know that the intended tone of Griffin’s tweet is “condescending.”

I’m certainly accustomed to being condescended to by folks who work in major media. In 2021, I think we all are. For instance, MSNBC invited me to come on its air a dozen times between 2017 and 2020, and yet it canceled on me without anything like a real apology each and every time but one (when I had to decline its invitation because I didn’t yet feel ready to speak on camera about the issue I was asked to speak about—Israel, which happens to be a particularly fraught topic for a non-practicing American Jew like me). I could have felt like having my time wasted in this way by a major-media company that wasn’t paying me for my time was condescending, but I opted to just tell my agent and publisher that I’d no longer accept invitations to appear on MSNBC. You can only let Lucy pull the football away from you at the last moment so many times, I figured. I did it eleven times, and I felt like that was more than enough for me.

At another point, a young man I won’t name, who was misrepresenting himself on Twitter as an MSNBC reporter, called me a “grifter” in a tweet. I angrily engaged with him publicly, wondering why MSNBC kept inviting me on-air if it considered me not just unreliable but dishonest. The “reporter” suddenly revealed himself to be an intern, not a paid MSNBC employee, so I withdrew from the conversation immediately—not wanting to have it out with someone I had just realized was likely college-student-age or thereabouts. Unfortunately, I pulled out of the conversation too late; somehow the Twitter exchange came to the attention of the President of MSNBC—I swear to you, not via me—and the intern was quickly released from his internship and sent home. I know this is what happened not just because of subsequent tweets by that intern (who wrongly decided I had taken action to affect his internship) but because the President of MSNBC called me personally to let me know that this had happened and apologize to me personally. I accepted that apology, admittedly flummoxed as to why MSNBC was suddenly so solicitous of my good opinion. Why not let me on-air one of the eleven times I was invited to do so, then cancelled on, if I was, as MSNBC’s President told me, considered a friend of the network and someone who the network admired?

At the time, the President of MSNBC—who I’m not naming here to not make it more of a thing than it was, but obviously you could Google it—asked that I keep our call private. At the time I agreed to do so, even though we weren’t involved in a journalistic exchange and, even if we had been, all of the statements he had made to me were made “on the record.” As time went on, however, I wondered about this bizarre request. Why was I asked to keep this apology from MSNBC a secret? Why did the president of the network laud me privately, when publicly there seemed to be some sort of institutional block against having me on-air? Why was a recently onboarded intern punished for falsely and maliciously calling me a “grifter” on Twitter, but no producer was ever told, “Hey, stop cancelling Abramson every time you invite him on?” I don’t have answers to these questions. But I tend to feel like whatever the answer is—in either the Griffin situation, or with the cancelled MSNBC invites, or my odd call with the President of MSNBC—somewhere encoded inside it is something about what’s wrong with media today.

One last note that I’d like to make in the body of this coda involves Rachel Maddow, who I have been and remain a fan of and whose show, The Rachel Maddow Show, I regularly watch. While on occasion, on subjects with respect to which I’m particularly knowledgeable—usually because I’ve researched them extensively for a book—I’ll find an error or two in Maddow’s journalism, which (genre-wise) is curatorial journalism like mine, it never affects my enjoyment of the program, or my respect for Maddow. That the official Twitter feed of Maddow’s blog followed me for almost the entirety of the Trump era was something that genuinely meant something to me.

The day the official Twitter feed of Maddow’s blog unfollowed me was the day I offered my first-ever criticism of Maddow’s program.

And it was a very mild one.

At the time, I was questioning whether it made sense to not only devote an entire hour to an interview with former Donald Trump lawyer and fixer Michael Cohen, but for journalists generally (including but not limited to Maddow) to so publicly fawn over Cohen and the prospect of interviewing him about his new book Disloyal. {Note: I have read that book and, candidly, I think it is excellent—though the question of who wrote it while Cohen was incarcerated, Cohen or a ghost-writer contracted with by him, remains open, in my opinion.}

In any case, Disloyal is a good book, and Cohen has a good story to tell. But it’s also one he told publicly—indeed on national television—before Congress. At the time America thought Cohen had told his whole story, but it later turned out that Trump’s former fixer had, perhaps in Trumpian fashion, withheld certain key details from Congress—not illegally, per se, but simply by way of not volunteering them as part of his presentation—so that he could seek a sentence reduction post-incarceration by proffering additional details of his work for Trump. While not the most honorable or smart move from a criminal defendant that I’ve seen in my legal career—all of which I spent representing criminal defendants—it was consistent with the benighted strategizing and sometimes silly posturing Cohen freely copped to in Disloyal. My point, in asking if Maddow had overplayed her hand or overhyped her upcoming interview with Cohen, was that there might be others she could interview who would be more likely to offer new and even more reliable info, even if they wouldn’t also bring the ratings of a Cohen interview.

Admittedly, having—at the time of that mild rebuke of Maddow’s program—written several national bestsellers in which Cohen’s activities, but also the activities of scores of other Trump agents, featured prominently, one of the many people I might’ve liked to see Maddow interview instead of Cohen was me. Maddow’s staff had been following my feed for years, I figured, and presumably (given that Maddow, her staff, and I had the same political preoccupations between 2016 and 2020) at least someone on her team had read my books or sections of them, so I wondered why Maddow had never so much as acknowledged my work while spending years discussing the very topics I had been writing about. Many readers of my Twitter feed wondered the same thing—though, frustratingly, some assumed that it was a lack of effort of my part that was behind my not appearing on Maddow’s program. The simple truth was that Maddow had not even 1% the enthusiasm for my work that she’d demonstrated for the prospect of interviewing convicted liar Michael Cohen on-air.

{Note: When I later did an interview with Cohen myself—in this case, after he’d asked me if I’d agree to be interviewed by him—some of my suspicions were confirmed. Cohen was charming, engaging to listen to, and clearly not only had great stories to tell but a particularly charismatic bravado in telling them. He also, it was clear, had a limited stock of such stories that he was willing to share and return to, and was far more comfortable reading from prepared notes than speaking off the cuff.}

In any event, my questioning of one decision made by Maddow’s bookers—the only time I can recall seriously questioning Maddow or her team, in the midst of years of lauding their work publicly and privately—turned out to be too much. The official Twitter account of Maddow’s blog unfollowed me immediately (within a matter of hours) after my critique appeared on Twitter.

I remember thinking at the time, “Wow—that was it? That was all it took?” I’d spent years supporting Rachel and her work, and years producing work that Maddow and her team might well have considered helpful, and the moment I spoke a word of critique, my years of research and encouragement were suddenly worth nothing at all?

I felt like I’d been provided a glimpse into the world of major media, where feelings are easily hurt despite all involved considering themselves professionals; where self-defeating grudges come easy despite the fact that the chief value amongst journalists and their staff should be access to reliable and relevant information; and where meaningful relationships between figures inside major media and figures outside major media, such as independent journalists, either (a) don’t really occur, or if they do, (b) have to occur on terms set and maintained and overseen on the “major media” end.

Conclusion

All this is my way of saying that I am, like my late father was, a “systems” guy. I try to analyze things at the level of the system. So it’s not just because of the differing responses of the Kremlin and Cracked to the recent article about me in Columbia Journalism Review that I say major media is profoundly broken. I saw it in my dealings with Chris Cuomo of CNN, Josh Meyer of Politico, and of course with disgraced journalist Lyz Lenz in the weeks after she was fired by the Cedar Rapids Gazette.

What all of these folks have in common is something I know a bit about: anxiety.

Far more than being attentive to the principles of journalism—which are damnably hard to perfectly adhere to, even under the best of circumstances—these people manifested a profound, abiding, and almost “mesmerized” focus on being accepted, respected, and permitted to remain in good standing within their professional class. Note that I say “professional class,” not “profession,” as it’s indeed difficult to detect much abiding concern with journalism among some of today’s most prominent major-media journalists. Far more evident, in the cases I’ve described and others, is interest in maintaining a death-grip on the status historically conferred by being a “journalist.”

Which, perhaps, is precisely the problem.

Always under-resourced and underpaid, major-media journalists now find themselves facing the trifecta: they’re at once under-resourced, underpaid, and under-appreciated.

Being a journalist just doesn’t have quite the cachet it once did, especially now that so much journalism happens in independent, semi-professional, decentralized spaces that aren’t controlled or even meaningfully influenced by the media scions of yore.

Today’s major-media journalists feel simultaneously so ill-used and worn by their own personal cares that every critique—and admittedly, they come fast and furious, now—feels like hot bacon-grease slathered on a gashing head wound. They worry, too, that to demonstrate any weakness is to be taken down by (now mixing my metaphors a bit) the barbarians at the gate. Needless to say, Kyle Griffin can’t be shown up by a Seth Abramson; Columbia Journalism Review can’t admit that an independent journalist it feels only contempt for does a much better and more consistent job of honoring contemporary journalistic mores and first principles than a self-declared media watchdog; the most popular program on MSNBC may deign to follow an independent journalist’s Twitter feed, but they’ll be damned if they’ll listen to even a single critique from that quarter. Cuomo and Meyer sure want the help of independent journalists—but not to credit them. Cuomo wants, too, for the very journalists whose help he won’t acknowledge to “send [him] love” on their Twitter feeds anyway, even as he gripes about not getting the same treatment from the barbarians as he feels Maddow does.

It is, as I said, a broken system—a degraded, devolved, and denatured system—and it is one I more and more find myself wanting nothing to do with, even as I still teach journalism at a public university. It’s a strange feeling, and perhaps explains some of the oddities in the first two entries in my new “university lecture series” at Proof (I, II).

There is something fragile, even brittle about some of today’s major-media journalists. It’s not that they don’t have a right to feel attacked—they do, as indeed they often are—but that one can’t both feel attacked and spend no time at all considering the critiques themselves. Major media doesn’t deserve all of the grief it comes in for, but it deserves some of it, and if it intends to do nothing to remedy the many ways in which it is and has long been degrading, devolving, and denaturing what was once widely thought of as journalism, perhaps it deserves even more grief than it receives. Really, though, what most of us who love and regularly consume major media even as we critique it want—in the same way we love and revel in being American citizens and living in America, even as we critique our country—is for things to improve. And right now I see no signs of improvement, or even signs that major media feels it must improve. Instead, we see a circling of wagons, a doubling down on past errors, a false haughtiness that offers only the thinnest veil between an increasingly dispirited public and a journalistic enterprise that I think on some hidden level knows it is failing itself and the rest of us.

For a long time, I wanted to “belong” in the world of major media. And if you were to read my biography and hear all the stories about my backchannel contacts with major media during the Trump era—scenario planning with Van Jones; private DMs with on-air talent at CNN and MSNBC; international phone calls with investigative journos working on topics I’d covered in the Proof trilogy—you’d probably think that in many respects I am part of that world. But I’m not, and I never really have been, and articles like those by Lyz Lenz are squarely intended to make sure I never will be.

Despite entering journalism 27 years ago, and over the years writing for and/or being interviewed by some of its biggest names—from The Washington Post to CBS News, The Economist to ABC News, Newsweek to The Dallas Morning News, The New Yorker to CNN and the BBC and dozens of others—it’s only now, decades on, that I realize that a space I once wanted to inhabit no longer holds much allure to me, and that I was foolish to so earnestly desire something of so little lasting value.

Journalism is complex and nuanced and heterogeneous and scary and a moving target. It requires a profound commitment to ethics—above all a degree of transparency and an interest in accuracy that is uncommon (the sort that would, respectively, prompt one to write an essay like this one and publish a book trilogy with 12,000 citations). But it also requires, much like several other professions I’ve worked in—the law, academia, publishing, criminal investigation, and poetry-writing—a degree of courage that is equally elusive and exceptional. Most days I don’t feel courageous, or act particularly courageously. But I know that I want to be courageous, and that at times I’ve exhibited that trait. And I know that almost every interaction I’ve had over the years with cable news, freelance think-piece writers, or major-media interviewers has left me with the distinct impression that journalism today does not especially value courage. Or daring, or idiosyncrasy, or a sort of integrity that’s pure and cantankerous and not particularly conducive to making friends. Journalism at the highest level feels today as though it is indistinguishable from Hollywood or (if you like) Washington politics, at a time when America needs it to be much more stringently committed to principles than the power-brokers of those broken ecosystems in D.C. and Los Angeles.

So what was this essay series about? Besides—quite obviously—a man who’s trying to process a traumatic event, it’s about a media watchdog publishing lies about me, knowing it was publishing lies about me, and then sending me abusive messages when I tried to get the sort of basic corrections any journalistic enterprise would have freely offered. The lies CJR maliciously published were then parroted by an American enemy, even as a humor website exhibited more decency and journalistic integrity in a matter of seconds than Columbia Journalism Review had in a matter of many, many months.

If that isn’t evidence that American journalism is broken, I really don’t know what is.

Seth,

The sad part is what you are pointing out, tRump was out there calling 'fake news.' Now, I know there is a major difference between your words and the words of an orange raping pig. I point this out because tRump would crime daily and get the *news* chasing their tail providing him with cover to escape under the radar. tRump manipulated the system he knew was broken and arrogantly taunted them. Now he is a total scumbag bottom of the pond sucking orange shit-stain, while you are a very honorable, noble person with integrity.

tRump was smart enough to know when people caught up with his bullshit and called out the broken system, he would be there yelling 'fake news' again, claiming it is what he meant while gaslighting, victim blaming, and playing the victim. He knew from the time during his criminal career the media was changing in a bad way (he is very old) and how to manipulate them. This is why they cannot stop wanting tRump back on so he can get them clicks, and these clicks would lead them to deriving their popularity in social media, much like the movie The Social Dilemma showed young girls get their positive self-image from *hearts/likes*. The way people are tracked online with what people click/link to, is monetized which means big businesses want to cash in on those spoils.

Cuomo and Maddow should not feel the need to perform like circus monkeys for a buck. I bet their contracts (pays) are based on their 'popularity' and go up and down accordingly. I have to wonder if the media outlets have bots/trolls fishing around looking for key words to bring them things to aggregate on their shows or even to help boost their ratings. Someone or something was watching all critical words which led to you (within hours) being unfollowed. I do have to wonder if that was an automatic computer AI response which unfollowed, or interns watching hundreds of thousands of people for potentially unkind words.

Some of this may be a little too far out there, Seth, but I am having fun coming up with possibilities. Please do not be critical of my grammar, I did not reread this after reading your article, it is raw running with it thoughts.

Best,